Information on COPD

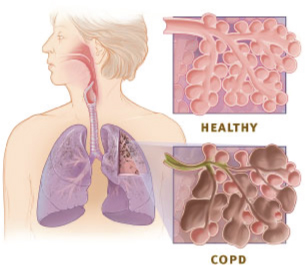

What is COPD?

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a lung disease that makes it difficult to breathe. COPD affects many aspects of a person's health. COPD is a preventable and treatable disease. Its pulmonary component is characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible even with the use of bronchodilator medication.

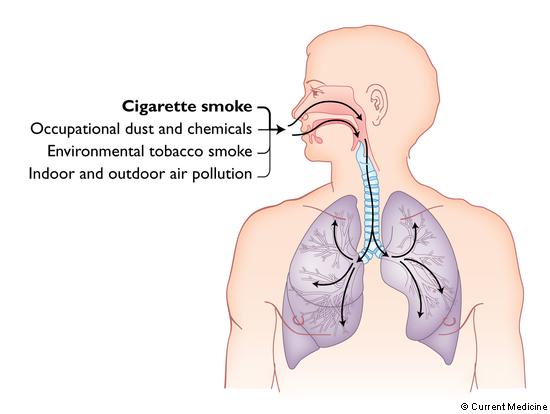

While cigarette smoking is the number one risk factor in developing COPD, other environmental and genetic risk factors can also play a significant role. Generally, COPD is the result of a complex interaction between environmental exposure such as smoking or breathing in fumes or chemicals and genetic factors. The interactions between these two risk factors, however, are not well understood.

There is currently no cure for COPD though medications are available to reduce symptoms. Getting treatment for symptoms can improve exercise capacity and increase quality of life. Avoiding exposures to risk factors that worsen COPD (such as cigarette smoke) are frequently employed to help manage the disease.

Prevalence of COPD

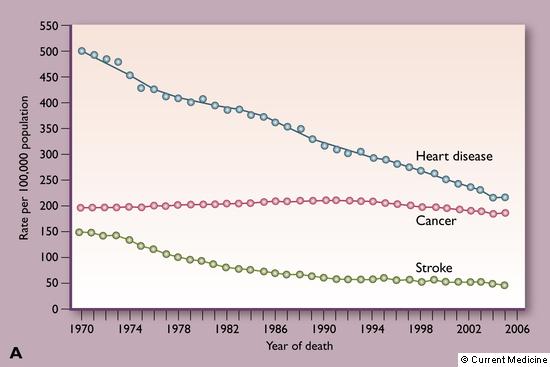

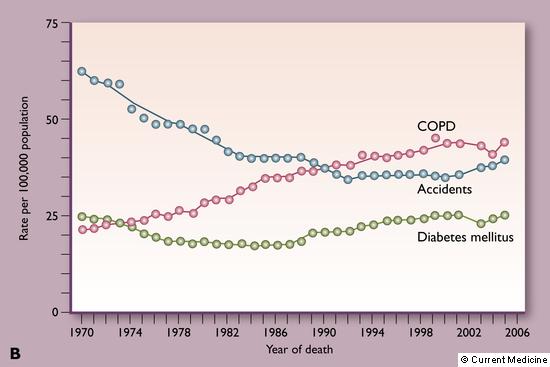

It is estimated that about 5 to 10 percent of adults may have COPD with an increase in prevalence with age. COPD and related conditions (including asthma) caused 130,000 deaths in 2005. Currently COPD is the third leading cause of death behind heart disease and cancer. Of the 10 leading causes of death in the United States, COPD is the only one to have increased in frequency over the past three decades. With more people being affected by COPD every year, understanding the causes and searching for cures has become increasingly more important.

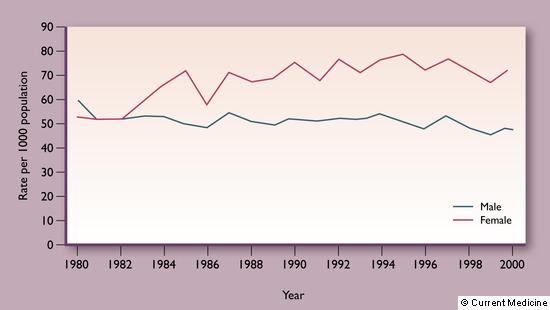

COPD may also be influenced by gender, race or ethnicity, and genetic factors. Historically, men have had higher prevalence rates of COPD than women; however, as shown in the figure below, there are currently more women with COPD, indicating that women may be more susceptible to the disease. Despite the higher occurrence in women, more men die every year from COPD. It is not yet clear if these differences are due to genetics or behavior as there are many possible factors that may contribute to disease outcome.

Characterization of COPD

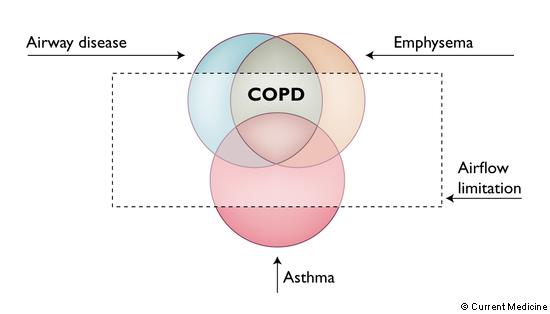

COPD is categorized by the presence two disease processes: airway disease (damage to the small bronchial tubes) and emphysema (destruction of air spaces in the lung). The lungs are composed of two major structural air conducting components: air passages and air sacs. In COPD there can be damage to either the air passages (airway disease) or air sacs (emphysema). Some patients have airway disease, some emphysema, and some a little of both. However, COPD is currently not defined by the anatomic or structural problems of the lung but rather by how well the lungs work. Lung function is identified by breathing tests called spirometry.

There is wide variation on how COPD can appear in a person. For instance, some people with airway disease or emphysema have normal lung function even though the lung looks abnormal on a CT scan. The current definition of COPD stresses the importance of the presence of airflow limitation as seen through a breathing test; thus, COPD is represented as the shaded area of the figure below.

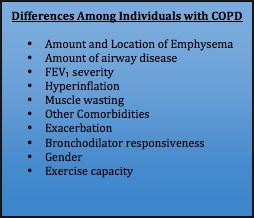

Many of the features of COPD can differ greatly between individuals (see table below). Because COPD can appear very different from person to person, it is sometimes misdiagnosed or overlooked in a medical evaluation.

Clinical Features of COPD

COPD affects many aspects of a person’s health. The figure below illustrates some of the more common clinical features that are seen in patients suffering from COPD. To use the figure, simply move your mouse over the clinical feature you wish to read more about and the definition will pop up over the feature.

Staging of COPD

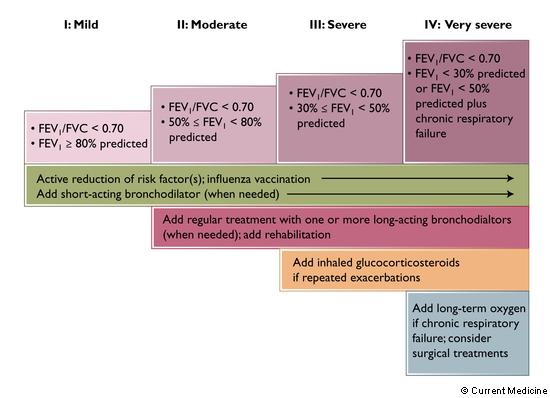

The variability in how COPD appears in people has led to a classification system that helps define COPD by the level of severity. The current classification of COPD involves four levels of increasing severity and is derived from the Global Initiative on Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines. Severity of COPD is currently defined by lung function as depicted in purple boxes below. Treatment is based upon severity of disease.

The current Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines for the treatment of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Therapy is step-wise as the patient's airflow limitation and symptoms worsen. FEV1 - Forced expiratory volume in 1 second;

FVC - forced vital capacity.

While the GOLD staging system has been useful to describe the severity of COPD for many physicians and patients, current research seeks to reclassify the severity of COPD based on other criteria. New classifications of COPD may include genetic factors and evaluation of lung health through the viewing of a patient's chest CT scan.

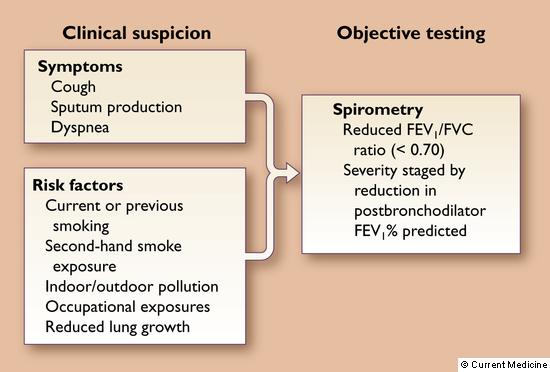

GOLD Diagnosis of COPD

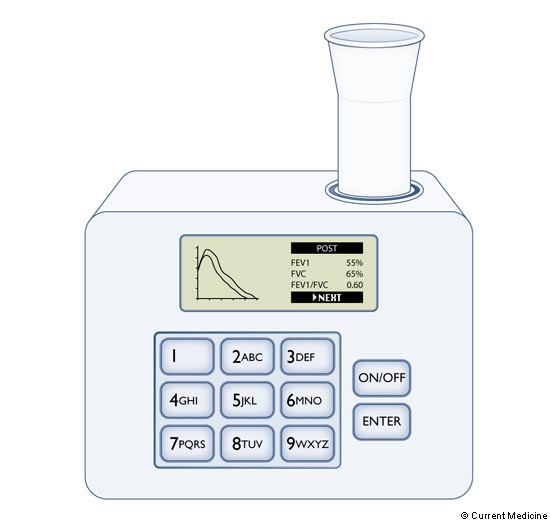

Diagnosis of COPD is essential as smoking cessation and pharmacologic therapy can greatly reduce the progression and morbidity of the disease. Diagnosis is based on spirometry. Spirometry is a non-invasive procedure where a patient is asked to exhale the air in his or her lungs through a device called a spirometer. The spirometer measures the amount of air that is exhaled and the time it takes for the lungs to empty out all the air.

An example of a hand-help spirometer. Spirometry can be easily performed in a doctor's office with small hand-held devices that are reliable and inexpensive.

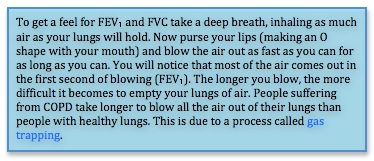

COPD is currently diagnosed by two numerical values that are assessed via spirometry: FEV1 and FVC. FEV1 is Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second, or the amount of air that can be blown out of the lungs in the first 1 second. FVC, or Forced Vital Capacity, refers to the total amount of air that a person can exhale.

Patients with COPD cannot blow air out as fast as healthy people. The total amount of air released in the first second is lower proportionate to the total volume of air the patient can exhale. Air coming out slower than normal is called airflow limitation.

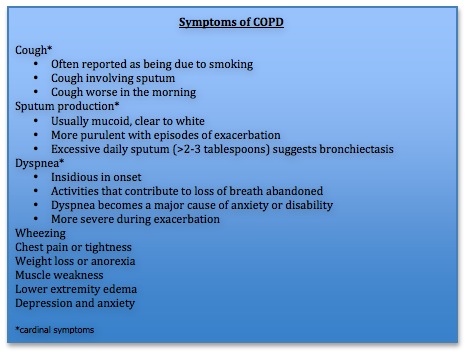

When considering COPD, physicians look for several key symptoms that serve as possible warning signs for the presence of COPD (see blue chart below). Dyspnea (shortness of breath) is the most common clear symptom of COPD, though cough is often the first to develop. Many scales can be used to classify the severity of dyspnea. The Modified Medical Research Council (MMRC) Scale is commonly used to assess dyspnea, and is also good at predicting long-term mortality associated with pulmonary disease. The MMRC assigns a grade or level of severity of dyspnea on a scale of zero to five, where zero means no breathlessness and five means too breathless to leave home or breathless when dressing.

In most cases, COPD is easily differentiated from other causes of dyspnea and cough. In some patients, however, it is difficult to determine if a person has COPD, asthma, or both.

When symptoms or risk factors exist, spirometry is performed.

Sputum: The mucus and other matter brought up from the lungs, bronchi, and trachea that one may cough up and spit out or swallow.

Dyspnea: Difficult or labored breathing; shortness of breath.

Understanding Airflow Limitation

Airflow limitation is currently the primary measure used to asses COPD and is defined as an FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7. Many other factors can contribute to a poor FEV1/ FVC ratio, however, such as asthma and the natural process of aging. In older patients especially, low FEV1/FVC ratios are more common and may lead to the over diagnosis of COPD. Asthma can usually be distinguished from COPD based on clinical features that are different from clinical features seen in COPD. Nevertheless, asthma may sometimes be difficult to distinguish from COPD.

Lung volume is also a key component of characterizing COPD. Measuring lung volumes is not required for the diagnosis of COPD; however, as the disease progresses, gas trapping and hyperinflation may develop which can be measured by lung volume assessments. Gas trapping occurs because the lung cannot empty fully due to narrow air passages as a result of COPD. In patients with COPD, the size of the lungs gets larger with disease progression as a result of gas trapping.

Hyperinflation can worsen with rapid breathing such as during exercise. This happens because the diseased lungs are not as efficient as normal lungs at emptying air and air gets trapped in the lungs. The process of increased gas trapping during exertion is called dynamic hyperinflation. Dynamic hyperinflation contributes to shortness of breath during physical activity.

Risk Factors in COPD

There are many factors that contribute to the development, severity, and disease progression of COPD. Some factors are largely controlled by a person's genes while others are greatly affected by harmful environmental hazards. In general there are two types of risk factors that can contribute to the development of COPD: environmental risk factors and genetic risk factors. Smoking is one example of an environmental factor that can cause and significantly worsen COPD.

Environmental Risk Factors

Toxins and particles that the lungs are exposed to through inhalation are considered to be environmental risk factors. Cigarette smoking remains the number one most commonly encountered risk factor in the development of COPD. Other environmental risk factors include lung infections early in life or low birth weight. Individuals of lower socioeconomic status have also been found to have an increased risk for developing COPD. The most significant environmental risk factors, however, are limited to those that involve inhaled particles. Some environmental risk factors are listed below.

• Cigarette smoking

• Inhalation of fine dust

• Inhalation of chemical fumes (paint, stains, and other chemicals)

• Indoor and outdoor air pollution

• Smoke from pipes, cigars, fire or other sources

• Socioeconomic status

• Early life infection and low birth weight

Reducing environmental risk factors is important in disease prevention and slowing progression. Smoking cessation is the single most important thing patients can do to reduce their risk for developing COPD. If COPD is already present, quitting smoking is the most effective and important action a person can take to slow the progression of COPD. Reducing exposure to other environmental risk factors such as dust and chemical inhalants may also be helpful in reducing symptoms and disease progression.

For information on programs to assist in smoking cessation, click here.

Genetic Risk Factors

Not all people exposed to environmental risk factors develop COPD. Individual differences among people play a factor in how each person responds to a risk exposure. Genes are the components of our DNA that make each person unique and likely play a major role in determining a person's individual response to cigarette and environmental risk exposure.

As we learn more about how COPD develops, the importance of the interaction between genes and environmental exposures is becoming increasingly clear. The genetic make-up of an individual can have a significant role in the development and presentation of COPD. One known example of a genetic risk factor is related to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. The COPDGene® Study is currently looking for other genes that contribute to the occurrence and progression of COPD.

Management of COPD

There are two major goals in the management of COPD. The first is to reduce symptoms, resulting in improved exercise tolerance and improved health status. The second is to reduce risk of disease progression, exacerbations and death. Physicians aim to monitor and manage a patient's COPD on an individualized basis and each patient of COPD may require a slightly different approach for the most effective management.

Many different treatment options may be used to help manage COPD and will vary widely depending upon the severity of the disease. Below is a list of possible treatment methods that may be employed by a physician.

• Smoking cessation - The most effective way to reduce symptoms and disease progression of COPD is to stop smoking. This action should be the first step in the treatment and management of COPD.

• Bronchodilators - Bronchodilators are used to treat the symptoms of COPD by opening up the airways so breathing is easier. There are several types of bronchodilators available and include: β2-agonists, anticholinergics, and methylxanthines.

• Steroids - Inhaled steroids can often be used to help alleviate the pulmonary inflammation that occurs with COPD. Chronic inflammation can cause a worsening of COPD and make it difficult to breathe. Systemic steroids (pills or injections) are often used to treat exacerbations of COPD.

• Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor - This type of medication can reduce the frequency of "flare-ups of breathing trouble," also known as exacerbations, that can sometimes occur in patients with COPD. This class of medication is effective in patients with severe COPD who also have chronic bronchitis and a history of exacerbations.

• Vaccines - Lung infections can significantly impact people already suffering from COPD and make their symptoms and general condition much worse. Preventing infection is key and can often be accomplished by getting a flu shot once a year. Obtaining a vaccination against the bacteria which most commonly causes pneumonia (pneumococcal vaccination) is typically recommended approximately once every five years.

• Antibiotics - The use of antibiotics if a lung infection does occur is critical to treating COPD exacerbations. Antibiotics are only used, however, if there is evidence that a lung infection is due to bacteria and not a virus or fungus.

• Rehabilitation - Pulmonary rehabilitation improves shortness of breath and the quality of life for a patient. Pulmonary rehabilitation takes a multidisciplinary approach to COPD and often includes the services of many health care professionals with different expertise. A comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation program often includes disease education, exercise training, and nutritional counseling.

• Oxygen therapy - In COPD, the lungs have a decreased ability to get oxygen into the blood. For patients with very low oxygen levels at rest, supplemental oxygen can significantly increase survival.

For more information on COPD, please talk to your physician or click here for online resources.

Information from this page was derived from the Atlas of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Desease with permission from James Crapo (editor) and Springer Science+Business Media LLC.